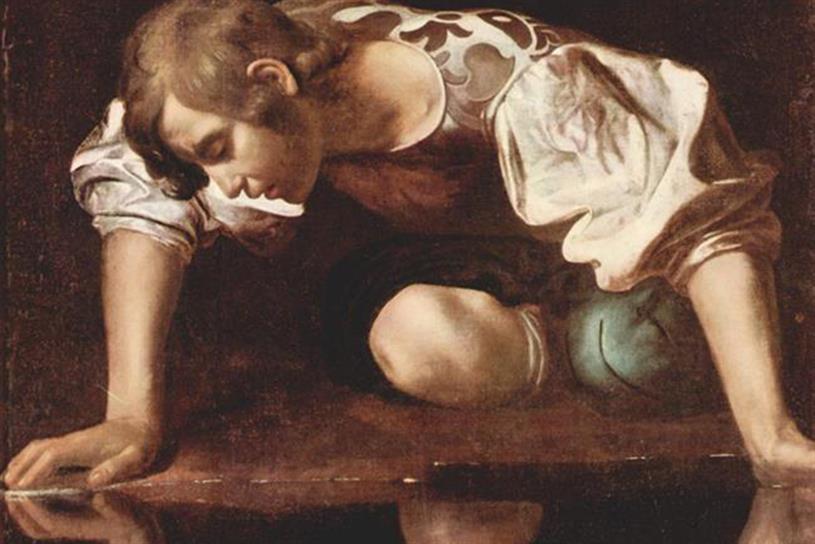

Ad narcissism: why our industry should put down the mirror

The author explains why advertising should end its obsession with the reflecting pool.

by Kate Nettleton

To continue enjoying this content, please sign in below. You can register for free for limited further access or subscribe now for full access to all out content.

Sign In

Trouble signing in?

Register for free

✓ Access limited free articles each month

✓ Email bulletins – top industry news and insights delivered straight to your inbox

Subscribe

✓ All the latest local and global industry news

✓ The most inspirational and innovative campaigns

✓ Interviews and opinion from leading industry figures